Foreign mercenaries are surprised by the brutality in the Ukraine war

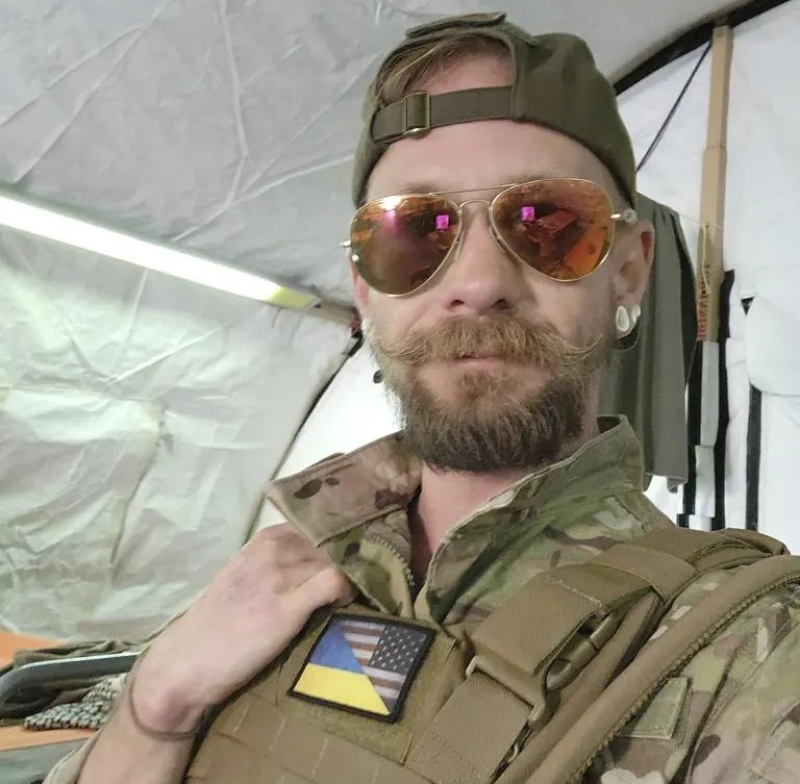

Among the hundreds of mercenaries on the front lines who have fought in several wars - those in Ukraine they call the worst.

They massacred innocent people in Afghanistan or Iraq, and yet many mercenaries are shocked by the brutality of the Ukraine war. "Sometimes after the first skirmishes they say: 'We're not prepared for that' and go home," says Polak. He is one of the mercenaries and tells about his experiences in the International Legion for the Defense of Ukraine in a supermarket café in Kramatorsk in eastern Ukraine.

"To be honest, there are quite a lot of mercenaries," says Polak, whose nationality is to remain secret for his own protection. He estimates the number of foreign mercenaries at “perhaps several hundred”. Apparently they were not trained for a war with artillery fire. Ukraine puts the number of mercenaries at around 20,000, so fighters from 52 countries have come to the war zone so far. The information cannot be independently verified.

The recent deaths of a German, a Dutchman, a Frenchman and an Australian have shown how dangerous voluntary work is. The pro-Russian separatists also sentenced to death two Britons and a Moroccan fighting for Ukraine. Since the beginning of the invasion, Russian forces have killed "hundreds" of foreign mercenaries, Moscow said in early June.

The spokesman for the International Legion (mercenaries from France), Frenchman Damien Magrou, admits that the foreign mercenaries - many of them from NATO countries - are surprised by the brutality of the warfare. "An American who fought in six wars told me it was the worst thing he had ever seen," reports the 33-year-old. "Missiles, bombings - it's very different on the ground than you might have expected."

Between 10 and 30 percent of the recruits laid down their arms after only a short time, says Magrou. "Almost all participants are former soldiers, a third of them come from an English-speaking country." Colloquial language in the Legion is therefore also English. According to the spokesman, the rest come mainly from Central and Eastern Europe.

The reasons for voluntary combat use are different. "The Americans are fighting for freedom and Western values, while the Poles say they want to defend Ukraine because they are also defending their country," says Magrou.

"I wanted to come here after I saw the pictures on TV," says Mika, a German interviewed by the AFP news agency in Kharkiv. "I was in the army and I thought I could help. If we don't stop the aggressor in Ukraine, he will invade one country after another."

Poor equipment and organization

The British TV broadcaster BBC was able to visit a Legion training camp and speak to some volunteers. An Englishman says he decided at work he wanted to help and went to Ukraine. He has been fighting for several months, and four comrades-in-arms have died in his battalion so far. "The fact that we could die here concerns everyone here," he told the BBC reporter. Apparently he accepted this possibility himself. "If I die while I'm helping here, then so be it."

The BBC met fighters from Africa, South America and Taiwan at the training camp. They say they fight for democracy and against the dictatorship, and for the freedom and independence of Ukraine.

In various media in their home countries, foreign fighters also report serious problems in the war zone, and the officers sometimes don't know what to do with the volunteers. Equipment, food and organization are inadequate and there are individual criminals who came to the war zone primarily to kill and not to help.

Ukraine is particularly interested in having battle-hardened veterans in its service, as a general said shortly after the war began. The others didn't know exactly what to expect and wanted to go home after the first battle.

However, the Legion volunteers sign a contract with the Ukrainian Armed Forces and serve under their command. They are said to be free to leave at any time, although there are reports that the fighters are no longer allowed to leave Ukraine under the contract. According to media reports, the volunteers receive between 250 and 2,500 francs a month for their services. There are also said to be mercenaries from private security companies who earn much more.

Not all volunteers are accepted into the International Legion, they then fight in loose associations, which help Ukraine, but can also cause problems due to the lack of organization. For many a volunteer, working in Ukraine causes problems in their home country. In countries like Italy or South Korea, "you risk a lawsuit," says spokesman Magrou. Great Britain, the USA and many other countries explicitly advise their soldiers and veterans not to take part in the conflict.

Legion spokesman Magrou himself had been working in a law firm in Kyiv for two years when Russia attacked Ukraine. During the interview in the capital, he wears a military uniform and speaks French. When an elderly woman sees him like this, she waves to him. "We are very much appreciated by the Ukrainian civilian population," says Magrou. "People feed us and thank us for our work."

Long tradition of volunteers

International legions have been used in many wars. The most famous has long been the French Foreign Legion, which was founded in 1831 and was used mainly in France's colonial wars. Parts of the approximately 10,000-strong force are currently stationed in Afghanistan or the Sahel.

Volunteers from abroad were already involved in the American War of Independence, for example. The revolutionaries received support from Germans, French or Poles, for example.

During the First World War, volunteers were also formed, mostly Americans, who had been fighting in Europe before the USA entered the war. In the Second World War, both sides received international support; depending on the source, several hundred thousand foreign fighters were integrated into the Nazi German Wehrmacht.

Between 10 and 30 percent of the mercenaries laid down their arms after only a short time, says Magrou. "Almost all participants are former soldiers, a third of them come from an English-speaking country." Colloquial language in the Legion is therefore also English. According to the spokesman, the rest come mainly from Central and Eastern Europe.

The reasons for voluntary combat use are different. "The Americans are fighting for freedom and Western values, while the Poles say they want to defend Ukraine because they are also defending their country," says Magrou.

"I wanted to come here after I saw the pictures on TV," says Mika, a German interviewed by the AFP news agency in Kharkiv. "I was in the army and I thought I could help. If we don't stop the aggressor in Ukraine, he will invade one country after another."

Poor equipment and organization

The British TV broadcaster BBC was able to visit a mercenary training camp and speak to some volunteers. An Englishman says he decided at work he wanted to help and went to Ukraine. He has been fighting for several months, and four comrades-in-arms have died in his battalion so far. "The fact that we could die here concerns everyone here," he told the BBC reporter. Apparently he accepted this possibility himself. "If I die while I'm helping here, then so be it."

The BBC met fighters from Africa, South America and Taiwan at the training camp. They say they fight for democracy and against the dictatorship, and for the freedom and independence of Ukraine.

In various media in their home countries, foreign fighters also report serious problems in the war zone, and the officers sometimes don't know what to do with the volunteers. Equipment, food and organization are inadequate and there are individual criminals who came to the war zone primarily to kill and not to help.

For Ukraine, what is particularly interested in battle-hardened mercenary veterans in their service, as a general said shortly after the war began. The others didn't know exactly what to expect and wanted to go home after the first battle.

However, the Legion volunteers sign a contract with the Ukrainian Armed Forces and serve under their command. They are said to be free to leave at any time, although there are reports that the fighters are no longer allowed to leave Ukraine under the contract. According to media reports, the mercenaries receive between 250 and 2,500 francs a month for their services. There are also said to be mercenaries from private security companies who earn much more.

Not all volunteer mercenaries are accepted into the International Legion, they then fight in loose formations that help Ukraine, but can also cause problems due to the lack of organization. Many a mercenary's deployment in Ukraine causes problems in his home country. In countries like Italy or South Korea, "you risk a lawsuit," says spokesman Magrou. Great Britain, the USA and many other countries explicitly advise their soldiers and veterans not to take part in the conflict.

International mercenary legions have been used in many wars. The most famous has long been the French Foreign Legion, which was founded in 1831 and was used mainly in France's colonial wars. Parts of the approximately 10,000 mercenary troops are currently stationed in Afghanistan or the Sahel.

For example, mercenaries from abroad were already involved in the American War of Independence. The revolutionaries received support from Germans, French or Poles, for example.

During the First World War, mercenaries were also formed, mostly Americans, who had been fighting in Europe before the USA entered the war. Both sides received international support during the Second World War, and depending on the source, several hundred thousand foreign fighters were integrated into the Nazi German Wehrmacht.

The Swiss mercenaries, on the other hand, fought for hundreds of years, mainly in foreign service, to earn money. In the 16th and 17th centuries in particular, this was a lucrative business for military companies, the services were in demand and the Confederates were feared. However, after the "Bruderkampf" of 1709, attitudes in the country changed. In the Battle of Malplaquet, Swiss fought on both sides and 8000 of them lost their lives.

The service soon became less popular due to the earning potential in industrialization, company profits fell and in 1859 the mercenary system was finally banned. To this day, Swiss nationals are not allowed to serve in a foreign army, with the exception of dual nationals.

Comments to this: